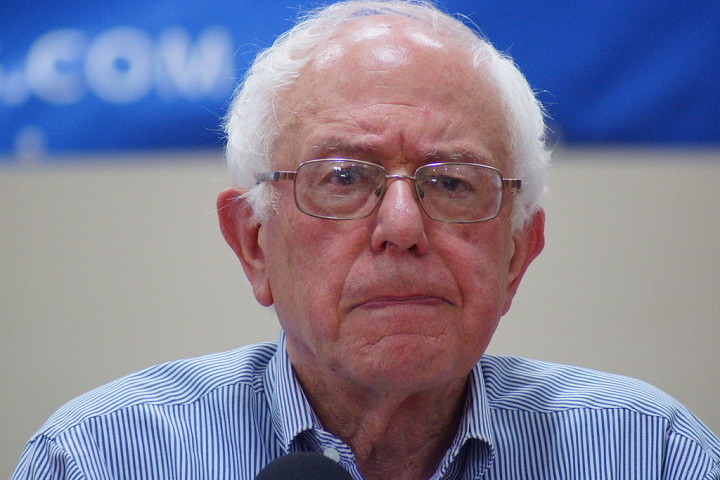

After Bernie Sanders’ big victory in New Hampshire, Danny Katch asks what it would take for him to win the nomination–and the even bigger challenge of winning the party.

WHEN THE loudmouths at Fox News used to warn about the threat of America being taken over by socialists, they probably weren’t thinking about people in Iowa and New Hampshire.

But with Bernie Sanders’ decisive victory in the New Hampshire primary on February 8, to go with his tie with Hillary Clinton in Iowa, the most support so far in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination has gone to a self-described socialist. No, it’s not the same as the imminent working-class seizure of the means of production, but Sanders’ unlikely surge doesn’t show any signs of slowing–and neither does the electrifying impact on Election 2016.

Sanders was always expected to do well in New Hampshire, next door to his home state of Vermont. But on Tuesday, he trounced the former Secretary of State and one-time prohibitive frontrunner by more than 20 percentage points.

As in Iowa, Sanders dominated among voters under 30, winning a lopsided 82 percent of the vote, according to exit polls. He had the edge among women, too, young and old–who Clinton supporters had alternately attempted to guilt and to shame into joining Team Hillary.

Sanders’ success is clearly based on widespread anger about economic inequality and insecurity–the urgently felt issues that always gets short shrift among mainstream political leaders. Even as the official unemployment rate dropped below 5 percent in January, wages have remained so low that more than half of U.S. households have less than $1,000 dollars in their combined savings and checking accounts–and a quarter has less than $100.

Six months ago, few observers–SocialistWorker.org included–thought that Sanders would be in the position he is today: leading among the convention delegates chosen by voters, with growing support against the candidate long anointed by the party establishment.

That’s because his campaign has become the latest explosive expression of class anger in America–another face of a radicalization that includes Occupy Wall Street, the protests of low-wage workers for a $15-an-hour minimum wage and the Black Lives Matter movement, to name a few examples.

In the face of the Bernie’s surge, Clinton supporters are coming off as entitled and out of touch–from the pundits who sigh that Sanders voters don’t seem to understand that our political system isn’t meant to actually get anything done; to the strange “feminist” appeals from rich and powerful women to young debt-ridden ones to do a sister a solid and help Hillary move into the White House.

Unlike Sanders’ success, the fact that Clinton has struggled to inspire anyone is no surprise. At a time when voters are in rebellion against the political status quo, Clinton’s message has always been that she should be elected president because she’s paid her dues climbing the ladder of that rotten system.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS in the U.S. aren’t about platforms or personalities so much as they are about paths. Campaigns carefully weave their candidate’s biographies and political beliefs into a symbolic narrative about the country we want to live in.

In 2008, Barack Obama thrilled millions with his story of an intelligent outsider whose unique perspective could bring white and Black people together to acknowledge and finally overcome the country’s long history of racism. It’s easy to smirk at how wrong almost every part of that sentence now seems, but a lot of the people doing the smirking, at least those old enough to remember, are lying to themselves if they claim they didn’t feel it at least a little bit.

This year, Bernie Sanders is inspiring voters with another narrative. He’s the last honest politician, the guy everybody laughed at as they got rich on Wall Street gambling, while he kept to his principles–even socialism!–until the day of financial reckoning came, and everyone realized he was right all along.

Like Obama’s, Bernie’s story doesn’t completely hold up–Progressive Punch ranks him as having only the 18th most progressive record in a Senate that he’s supposedly leading a revolution against. Sanders may champion single-payer health care against the mess that Obamacare made of an already messed-up system, but Senator Sanders did the “realistic” thing in 2010 and voted for the Affordable Care Act.

Still, the narrative is grounded in enough reality to work.

The story that Hillary Clinton tries to sell is that she’s a strong woman who endured decades of sexist abuse, but always got back on her feet to fight for the underdog. Her problem is that most Democratic base supporters only buy the first part of her story. They may admire her toughness in standing up to Republican abuse, but they think the cause that’s always driven her is naked ambition to advance her career–and that of her husband, who happens to be a sexist pig, which has always complicated the first part of the story.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

THE PRIMARY contests have only just begun, and the odds are still against Sanders winning the Democratic nomination for president.

That’s not because, as the mainstream media lectures, his message of universal health care and free college tuition is somehow against the values of a majority of Democratic primary voters, but because he is starting from way behind in many states–and even if he manages to pull even with Hillary Clinton, he has to face the gauntlet of the Democratic Party establishment and the corporate media.

Here’s some of what Sanders has already overcome. Up until recently, he’s had very little media coverage, far disproportionate to his popularity. According to the Tyndall Report, during 2015, ABC’s flagship World News Tonight program devoted 81 minutes of coverage to Donald Trump, while giving Bernie Sanders just 20…seconds.

Then, after Sanders steadily gained ground in the lead-up to Iowa, the media coverage changed. Now, he got attention from the press, but the stories and segments were about how he was doing so well right now because Iowa and New Hampshire are part of his natural base–being well-known hotbeds of communism, of course.

On the other hand, national media attention was sorely lacking about the irregularities in the Iowa caucuses that might have unfairly kept Sanders from winning–and we’re not talking about Hillary Clinton’s campaign winning six out of seven coin flips, an odds-defying rate that suggests she might be employing the dark forces of New England Patriots coach Bill Belicheck.

More serious were the allegations of recording errors, including one caucus district where only one person showed up, voted for Sanders, and then found out his district was recorded as a Clinton vote. Afterward, the Des Moines Register editorial board concluded that “Something Smells in the Democratic Party.”

The state party, led by Clinton supporter Andy McGuire, has refused to release the raw totals from the caucuses so people can see if Sanders had the most supporters overall.

That’s at the state level. Then there is the issue of “superdelegates” to the Democratic National Convention that will officially pick the nominee. Some 712 out of the 4,763 delegates aren’t selected in primary contests, but get their seats based on being an officeholder or party insider.

So far, 359 superdelegates have already pledged to vote for Clinton, versus 14 for Sanders. In other words, Sanders will have to do much better than win a majority of primary voters–he has to overcome the head start that Clinton has by virtue of being the nearly unanimous choice of the party establishment.

Clinton’s attacks on Sanders, which began in earnest when Sanders started coming closer and closer in Iowa, haven’t worked yet. But they’ll keep trying new ones to see what sticks.

Don’t be surprised as the South Carolina primary approaches at the end of the month to hear Clinton allies imply or state outright that there is something racist about Sanders criticizing any of Barack Obama’s policies. If it happens, that will be particularly ironic since it was the Hillary Clinton campaign in 2008 that actually did pander to racism in the hopes of stopping Obama–like when the candidate herself questioned whether Obama would be able to win support from “hard-working Americans, white Americans.”

Meanwhile, the Clinton campaign will continue to roll out prominent liberal figures to pile on against Sanders. It’s a sign of how tight a grip Clinton has on the party hierarchy that liberals like New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio or Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown are behind her, rather than Sanders, even though he is much closer to them politically.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

IF SANDERS can hold up under the pressure of the coming months and continue winning the same level of support from primary voters and caucus-goers in other states, then things will get interesting.

His continued success will further alarm the likes of Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein–Clinton has been courting support from Wall Street for many years, despite her occasional bouts of watered-down populist rhetoric. (Unfortunately, given Sanders’ thoroughly mainstream positions on foreign policy, including support for the “war on terror,” the military-industrial complex won’t have as much reason to be alarmed.)

But the impact of a continued and widening groundswell of popular support for Sanders could go further and shake things up in many liberal organizations, such as NARAL Pro-Choice America and the Human Rights Campaign, which reflexively endorsed Clinton without ever considering what supporters thought.

Can Sanders actually win enough votes in the primaries to win the Democratic presidential nomination? He still has to be considered a big underdog–if nothing else, then because of Clinton’s superdelegate advantage. But it can’t be entirely ruled out so far in advance, and with so many unpredictable factors–including the potential for the Clinton campaign to self-destruct, either as a result of its clumsy attacks on Sanders or one of the many scandals that have attached themselves to the Clintons over the years.

But Sanders supporters need to ask themselves another question: If Bernie Sanders could manage to win the Democratic Party presidential nomination, can he win the Democratic Party to support anything he stands for?

Count House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi as a “no” on that one. Last month, she lectured Iowa caucus-goers that there is “no use having a conversation about something that’s not going to happen”–meaning Sanders’ proposal for single-payer. It was an unsubtle message to the Sanders’ campaign and its supporters that the agenda of the Democratic Party isn’t going to be decided democratically.

As SocialistWorker.org wrote in an editorial:

Sanders’ insistence on talking about health care is a breath of fresh air in the post-ACA political climate. But it is, in fact, unrealistic to propose a single-payer health care system as a candidate of a party that is just as much in the pockets of the insurance and pharmaceutical industries as the Republicans. Were Sanders ever to find himself in a position of trying to achieve single-payer, his own party would stab him in the back.

Sanders says he wants to bring a “political revolution” to Washington, but what does that really mean? When he defines it, he usually means that the groundswell of support to get him elected would also usher in a Democratic majority in the Senate and House, which could enact his progressive policies and get money out of politics.

But even in the unlikely event of a Democratic sweep of Congress, Sanders’ “revolution” depends on the party supporting his platform–while its leadership makes clear every day that it doesn’t. It’s never a good idea to go into battle against the richest and most powerful oligarchy the world has ever seen alongside comrades who tell you to your face that they don’t have your back.

The betrayals would begin long before the next president and Congress are sworn in. In 1972, liberal George McGovern won the presidential nomination over the opposition of party leaders–and the Democratic establishment sat on its hands to make sure McGovern lost the general election against Richard Nixon.

Those are some of the obstacles Sanders faces if he hopes to win not just the Democratic presidential nomination, but control of the party itself. But recognizing the difficulties in overcoming them shouldn’t take away from recognizing the impact his campaign has already had and will continue to have in the coming months.

Sanders’ campaign has rekindled the spark of rebellion that has been flickering since the Great Recession hit. It’s up to all of us to build the organizations and social movements that can shield the flame from those who will try to extinguish it–starting with the leaders of the party in which Sanders has chosen to run.