Titled, “Somber reflections on the last days of the Pacific War at the ‘Chapel of the Thunder Gods'”, Hong Kong-based journalist Steven Knipp was published in Time on this day marking the 70-year anniversary of Japan’s surrender.

(Extracts follow, for the full article see: http://time.com/4021062/japan-kamikaze-ww2-museum/ )

In recent weeks, all across Asia there have been countless ceremonies, somber and solemn, to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of the World War II in the Pacific. This titanic struggle officially came to a close on the battered, sun baked deck of the U.S.S. battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay, with the Japanese military signing their surrender papers on Sept. 2, 1945.Tokyo’s defeat is being marked today in Beijing, where a massive military parade commemorates the 70th anniversary of what is known as the Victory of Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. Far away, in the sleepy rural town of Chiran, in Japan’s lush southern prefecture of Kagoshima, another, far quieter ceremony has been held. Its location? The little-known Chiran Peace Museum.

[…..]

In an attempt to boost morale, Japanese military commanders (themselves tucked safely away in bunkers in distant Tokyo) proclaimed the young pilots “thunder gods,” declaring that after the thunderous explosion of their airlines, the young men would become divine spirits. Japan’s imperial command also bestowed on the fliers the term kamikaze — divine wind — a reference to the fierce typhoon winds that saved Japan from attacking Mongol fleets in the 13th century.

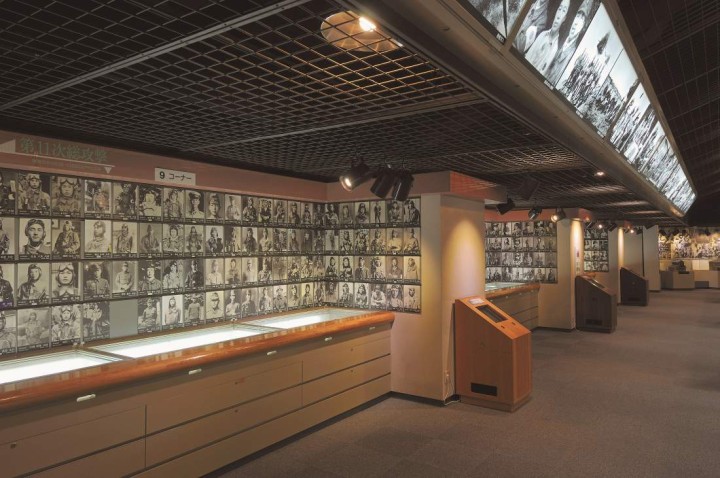

Inside the museum are a number of World War II Japanese aircraft. But what catches the eye of most visitors are the many spotless display cases that hold such kamikaze artifacts left behind: notebooks, goggles, diaries, wristwatches and handmade dolls given to the pilots by female relatives. Lining the museum’s walls are hundreds of black-and-white photos of the young pilots, each with a name and date of death, in the order that they died. One of the most poignant photos shows five fliers holding a puppy. While the labels are in Japanese, foreign visitors will have no trouble reading the emotion in the eyes of the pale young men as the gamely pose for a last toast before climbing into what were essentially their flying coffins.

[…..]

There’s no question that the suicide missions aroused complex feelings in the young kamikazes. Some of the museum’s artifacts hint at the pilots’ torment. Letters bidding farewell to mothers, fathers, and sweethearts convey the writers’ great sadness at having to die so young, as well as their devotion to both family and homeland. Some of the letters, written by the pilots on their final night on earth, can be read in English via touch screens. Just outside the museum, in a small shady cedar forest is a (restored) army pilots’ house where the kamikazes would stay until being sent out on their final missions. Here the young flyers would write short messages or pen farewell notes and letters to be their parents or loved ones. While most foreign visitors to the museum are well aware of the countless atrocities carried out by the Japanese in China and across East Asia, it is not difficult to see that these young flyers were also pawns controlled by Japan’s hard-core military regime.

At the entrance of the Chiran Peace Museum, the purpose of the facility is stated as “to commemorate the pilots and expose the tragic loss of their lives so that we may understand the need for everlasting peace and ensure such incidents are never repeated. That is now our responsibility.”