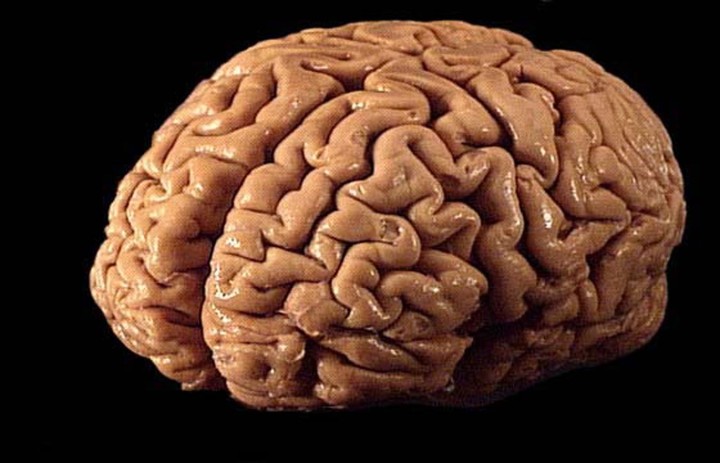

Visualization results in the activity in certain areas of the brain, providing pictures based on our memories of how things or people look.

The process takes place in the frontal and parietal lobes, which “organize” the visualization, with the temporal and occipital lobes “summoning” the things we want to see in the mind’s eye, and giving them a “visual” feel.

Thus, aphantasia can be caused by a failure in a part of this network, but the issue has never been explored in so much detail before.

As long ago as the 1880s, British scientist and polymath Sir Francis Galton first spoke of the phenomenon, and another 20th century research suggested that the inability to visualize may occur in about one in 40 of the population.

Now cognitive neurology professor Adam Zeman and his team of researchers at the University of Exeter Medical School are trying to discover why people aren’t able to visualize memories, things and people: In other words, why some people just don’t have a “mind’s eye.” The term aphantasia was coined in the team’s article in the Cortex journal.

The curious fact is how the research began: US science journalist Carl Zimmer wrote an article in Discover magazine, focusing on a paper by Zeman.

The paper concentrated on a man who lost his mind’s eye in his sixties after a cardiac procedure. After Zimmer’s article was published, 21 people reached out to Zeman, saying they had had a similar experience. They never had a mind’s eye in the first place, though, they said.

Zeman decided to describe these cases, and the article in the Cortex journal on the phenomenon was the result.

“This intriguing variation in human experience has received little attention,” Zeman said in a statement. “Our participants mostly have some first-hand knowledge of imagery through their dreams: our study revealed an interesting dissociation between voluntary imagery, which is absent or much reduced in these individuals, and involuntary imagery, for example in dreams, which is usually preserved.”

The condition can significantly influence a person’s life, the study’s responders have demonstrated.

25-year-old Tom Ebeyer from Ontario, for instance, began to feel “isolated” when he discovered that his girlfriend sees things in her mind’s eye, and he doesn’t.

“The ability to recall memories and experiences, the smell of flowers or the sound of a loved one’s voice; before I discovered that recalling these things was humanly possible, I wasn’t even aware of what I was missing out on. The realization did help me to understand why I am a slow at reading text, and why I perform poorly on memorization tests, despite my best efforts,” Ebeyer said.

The whole experience had a “serious emotional impact” on him, he said.

Ebeyer’s mother died a few years ago, and he couldn’t picture the things they did together – factually, he remembered, but there was no visualization.

“To have the condition researched and defined brings me great pleasure,” Ebeyer said. “Not only do I now have an official title to refer to the condition while discussing it with my peers, but the knowledge that professionals are recognizing its reality gives me hope that further understanding is still to come.”

Another study subject, 39-year-old Neil Kenmuir from Lancaster in northwest England, first experienced the condition in primary school, and understood that he couldn’t visualize the sheep needed for “counting sheep” before he went to sleep.

Neil is a voracious reader, but avoids books with a lot of descriptions, as to him they seem meaningless.

“I just find myself going through the motion of reading the words without any image coming to mind. I usually have to go back and read a passage about a visual description several times,” he said, in comments reproduced in Zeman’s statement.

Zeman insists that aphantasia is “not a disorder,” and he estimates it may affect up to one in every 50 people.