Iran and the group of six world powers have about one month to make history and reach a comprehensive agreement to end the standoff over Iran’s nuclear program. Officials in Tehran have already indicated that they would be open to the possibility of extending the talks for some time beyond the June 30 deadline, so that there’s opportunity for negotiating if there are still points of disagreement that need to be worked out. However, the hawks and peace-haters don’t sit back idly and try their best to throw a spanner in the works of the diplomats striving for making peace and concluding one of the lengthiest diplomatic marathons in the contemporary history.

By: Kourosh Ziabari

On Thursday, May 7, the U.S. Senate voted overwhelmingly to endorse the Iran review bill that would require President Obama to submit any final deal with Tehran to the Congress for final confirmation. According to the Corker-Cardin legislation, the Congress will have 30 days to approve the agreement or vote in disapproval.

On the other corner, the Israeli government and the influential Israeli lobby in Washington are putting pressure on President Obama to compel him to leave the nuclear negotiations with Iran and pursue a military option instead.

A noted American journalist tells Iran Review that any Iran-U.S. rapprochement following the possible conclusion of the nuclear deal will weaken Israel’s influence in the Middle East and Washington, and that’s why they’re pulling out all the stops to make sure that there would be no arrangement and deal by the June 30 deadline.

“Israel and its more right-wing supporters here naturally want to weaken those states that are hostile to Israel and strengthen those states that are more friendly to it,” he said. “They fear that, given Iran’s large and relatively well-educated population, as well as its support for Hezbollah, in particular, the lifting of the sanctions regime that has been imposed against it will significantly increase its power and influence in the region to Israel’s detriment.”

Mr. Jim Lobe believes that a nuclear agreement would mean a fundamental change in the anti-Iran discourse propped up continuously in the last 4 decades.

“The fact is that Israel and the GCC have benefited tremendously over the past 35 years by U.S. efforts to oppose and isolate Iran, and the nuclear deal signals a fundamental change in their position,” he stated.

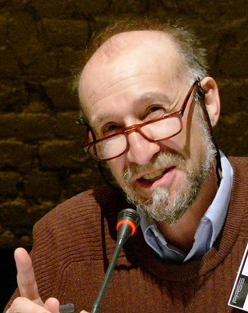

Jim Lobe runs the political blog “Lobelog” where several major diplomats, authors and analysts write on the most pressing foreign policy issues facing the United States, particularly in the Middle East. He is the Washington Bureau Chief of the international news agency Inter Press Service and is widely cited for his critical analysis of the Iran-U.S. relations.

Iran Review talked to Jim Lobe about the latest developments surrounding the nuclear talks and the repercussions of a possible agreement between Iran and the EU3+3, including the United States.

Q: The recent letter by the 150 Democratic members of the House of Representatives expressing support for diplomacy with Iran and the finalization of the nuclear agreement can be seen as an encouragement for the Obama administration to stand steadfastly and seal the deal in the face of domestic pressure. How is the balance of power in the United States, between the government and the two chambers of the Congress? Do they have the capability to take a consistent and coherent decision regarding the comprehensive agreement with Iran? President Obama’s endorsement of the bill that would oblige him to submit any deal with Iran to the Congress for approval will surely lengthen and complicate the process of finalizing the nuclear agreement with Iran, and this might sound disturbing to the Iranians. Will the Congress ruin the deal with its interventions?

A: It’s not so much a question of the balance of power between the administration and the two houses of Congress; it has much more to do with partisan politics. The Republicans, which have moved even farther to the right since the end of the George W. Bush administration, are, with a few exceptions, opposed to any agreement with Iran, and then have a majority in both houses. As a result, they can pass bills that formally disapprove of any deal that may be reached between the U.S. and Iran as part of the P5+1 process – as provided in the recently approved Corker-Cardin legislation, or make it impossible for the administration to comply with various aspects of such a deal, such as denying funding that would be needed by the administration to actually implement the deal or denying Obama authority to waive certain sanctions. If such legislation is approved by both houses, then the question becomes whether any veto cast by Obama against such legislation can be sustained in either house of Congress. Under the U.S. Constitution, a presidential veto can only be overcome if two third of each house votes to override it. Thus, if 34 or more Democrats in the Senate or 145 or more Democrats in the House of Representatives vote to sustain the veto, such legislation cannot become law. That is why the 150 (now 151) Democratic members –although several of those who signed the letter are non-voting members of Congress – who signed the letter is significant. If they vote to sustain a presidential veto, then no legislation designed to sabotage a P5+1 deal can become law, and Obama can proceed based on existing legislation and his executive authority under the Constitution.

Under the Corker-Cardin bill, which passed both houses and was signed by Obama into law last week, Obama will be unable to waive certain sanctions for at least 30 days while Congress decides if it wishes to pass a resolution disapproving or approving the prospective deal or to simply do nothing. The administration, however, is confident this will not lengthen or complicate the process of finalizing an agreement because Iran will require some time – well over one month, to actually begin to implement its provision.

Of course, it remains possible that Congress could still sabotage a deal by approving other legislation that will be supported by a sufficient number of Democrats in both houses of Congress to override any presidential veto. At this point, however, such a scenario is unlikely unless there is some unforeseen event or provocation by Iran or a third party that would make it politically impossible for Obama to either veto any deal-breaking legislation or for such a veto to be sustained by Congress. For example, if it was believed that Iran was responsible or played some significant role in a major terrorist attack against a U.S. target or that of a close U.S. ally, then any deal would likely be derailed.

Q: While you talk about a possible move by Iran that can derail the talks, I’d like to mention that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has confirmed a number of times that Iran has complied with its commitments under the terms of the Geneva interim accord (Joint Plan of Action) – the first step on the path of a comprehensive Iran-U.S. nuclear agreement, signed on November 24, 2013. So, it’s already clear to the United States that Iran will abide by what it officially agrees to. Then, why is it haggling over such details as the timing of the sanctions removal, even though the Lausanne framework deal made it clear that all the unilateral, multilateral and UNSC-endorsed nuclear-related sanctions will be terminated following the implementation of the comprehensive deal?

A: First, past compliance with one agreement does not by itself ensure future compliance with a second agreement, so, just as Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has continued to express great skepticism about Washington’s good faith and compliance with any future agreement, so it is natural for the U.S. government to maintain a skeptical attitude about Iran’s future compliance as it would with any government with which it has had a mainly adversarial relationship for so many decades. Both sides have noted the existence of great distrust between them despite the apparent success of the implementation of the JPOA. Second, I believe the precise timing of the lifting of the various nuclear-related sanctions remains a subject of negotiation, although the administration appears confident that this will not prove to be a problem that jeopardizes the successful conclusion of a deal.

Q: There’s something regarding the sanctions that I’ll need to bring up. It was maintained some 3 years ago, just prior to the election of President Rouhani, that the sanctions were slapped on Iran to bring it to the negotiation table and force it into making compromises. Now, Iran is at the negotiation table, but as its officials say, not simply because of the sanctions. However, it sounds like the sanctions have turned into an end, not the means, and a bargaining chip. What has been largely overlooked is that the Iranian government is willingly cooperating with the P5+1 and is ready to come up with meaningful confidence-building and transparency measures. So, what we hear every day is that new sanctions are being imposed under different pretexts, and their removal is being conditioned on further concessions by Iran. Do you consider this loop to be fair and equitable?

A: I’m not sure what precisely you are referring to in this question. If it is a matter of additional sanctions being imposed now and then against specific companies and individuals because of their alleged violation of existing law, then that can be explained both as a legal issue and a political one. Legally, the U.S. is still applying sanctions according to U.S. laws. Politically, the continuing application of sanctions for alleged violations demonstrates to anti-Iran hard-liners in both parties that the administration remains committed to enforcing sanctions against Iran. That makes it easier for many Democrats, in particular, to remain loyal to the administration on the much bigger pending issues regarding eventual approval of or acquiescence in a comprehensive deal.

If you are referring to “new” sanctions being imposed against Iran, no new sanctions legislation has passed Congress since the Geneva agreement. New sanctions legislation has been introduced by Iran hawks – particularly those close to the Israel lobby – over the past 18 months but has not been approved due to the administration’s threat to veto any such legislation and a sufficient number of Democratic lawmakers who have opposed it. In fact, the administration has repeatedly made precisely the point included in your question: that the sanctions should be treated as a means to reach a deal and not an end in themselves. Sanctions have indeed been used as a bargaining chip to provide an incentive to Iran to make compromises, just as Iran has used its growing nuclear infrastructure as a bargaining chip to provide the U.S. and its P5+1 partners to make compromises regarding their acceptance of a sophisticated nuclear program.

Q: In one of your recent articles, you expounded the reasons why the anti-Iran group UANI, which I believe is founded upon the objective of defaming Iran and crippling its economy, not simply over the nuclear case, but also on human rights violation charges, is now distancing itself from the expert analysis of some its leaders, including Gary Samore, especially following the Lausanne framework deal of April 2, which was welcomed worldwide. If UANI, AIPAC, JINSA and others want to see Iran would not obtain nuclear weapons, then their expectation is being already fulfilled through the Geneva interim accord, and the anticipated comprehensive deal to be sealed by June 30. What more are they looking for?

A: With respect to the organizations that you cite in your question, I believe they are very much part of what we sometimes call the Israel lobby, that is very responsive to the concerns of Israel’s political leadership. As everyone knows, Netanyahu has expressed very strong, often apocalyptic concerns, about Iran’s nuclear program and its purported future intentions against Israel. These organizations have consistently echoed and amplified those concerns, although, as you point out, there are internal differences of opinion within them. Samore, for example, has been far less hawkish than the organization for which he serves as president. JINSA has an Iran task force co-chaired by a former senior Obama official, Dennis Ross, and a former Bush administration official, Eric Edelman, and, within that task force, there is some disagreement over whether the United States should acquiesce in a limited uranium enrichment program in Iran or should support Netanyahu’s more extreme demands. When you ask what more they are looking for, I think the answer is ultimately what they fear is not so much that Iran will develop a nuclear weapon that will be used to attack Israel, but rather that any rapprochement between the U.S. and Iran will weaken Israel’s influence both in the region and in Washington DC. Israel and its more right-wing supporters here naturally want to weaken those states that are hostile to Israel and strengthen those states that are more friendly to it. They fear that, given Iran’s large and relatively well-educated population, as well as its support for Hezbollah, in particular, the lifting of the sanctions regime that has been imposed against it will significantly increase its power and influence in the region to Israel’s detriment.

Q: So, you believe Israel will suffer if a comprehensive deal between Iran and the six world powers is concluded. True? There are people who believe that the peaceful settlement of the nuclear controversy will gradually turn the public attention to the Israeli occupation of Palestine and the settlement constructions. Do you agree with this premise?

A: As explained [in the previous questions], I believe Israel’s leadership fears that the end of the sanctions regime will significantly increase Iran’s power and influence in the region to Israel’s detriment. And, so long as the Islamic Republic remains hostile to Israel and supports Hezbollah and other groups hostile to Israel, Israel wants to keep it as isolated and weak as possible. Of course, your suggestion that an end to the nuclear controversy will also tend to permit a greater public focus on Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories is correct, but I don’t think that is the primary motivation for Israel’s strong opposition to a nuclear deal that could lead to a U.S.-Iranian rapprochement. It is a factor; but I don’t believe it is necessarily the most important one.

Q: The Arab states in the region also share Israel’s concerns, I think. What do you think about the growing apprehension of the Arab monarchies of the Persian Gulf regarding the possibility of a nuclear agreement between the United States and Iran? Are they afraid that the deal will lead to the rise of Iran’s economic power and political clout in the region? Was it the reason Obama tried to appease the GCC leaders in the Camp David summit and assure them relations with Iran will not be normalized soon?

A: The apprehensions of the Arab monarchies are similar to those of Israel. They believe that an end to the sanctions regime against Iran will necessarily increase its influence in the region, a development they fear for many reasons, not the least of which are historical – Persians vs. Arabs, sectarian – Shiite vs. Sunni, and the fact that these states are small, in some cases very fragile [such as] Bahrain, almost completely lacking in democratic governance, politically sclerotic, and almost entirely reliant on Western powers for security. At the same time, they are important players in the international economic and financial system; several of them host important U.S. bases that the Pentagon considers essential to retain its conventional military dominance in the region; and they have generally proved helpful in serving a variety of U.S. interests. Thus, Obama does not wish to be seen as abandoning them in favor of Iran. He has a very narrow tightrope to walk: he must reassure the GCC and Israel and its supporters here, while seeking a rapprochement with Iran in order to achieve of what he has referred to as an “equilibrium” in U.S. relations between Iran and the GCC and Israel.

Q: Finally, how do you see the political future of the Middle East in the light of the recent advancements of the ISIS in Syria and Iraq, the continued military involvement of Saudi Arabia in Yemen, the ongoing nuclear talks between Iran and the six world powers and the worrying tensions between Russia and the West?

A: I think Obama will try to achieve an “equilibrium,” as mentioned above, that will permit some greater cooperation with Iran in containing and defeating ISIS, especially in Iraq, while offering limited support to anti-Assad forces – but not ISIS or al-Nusra in Syria. He would like to bring Iran into the Geneva talks in hopes that some kind of political settlement can be reached on Syria between Riyadh, Doha, and Ankara, on the one hand, and Tehran and Moscow on the other that will eventually remove Assad, weaken ISIS, and wind down the civil war. Washington has already been pushing hard on Riyadh to reduce its air campaign in Yemen and make a serious effort to reach a political settlement there. Ultimately, I think the administration wants to create a new regional security structure that includes Iran and achieves the kind of “equilibrium” I referred to. Whether he can achieve any or all of this, however, is highly doubtful, particularly given the hawkish policies and personalities of the new regime in Saudi Arabia which appears to have significantly hardened KSA’s anti-Iranian stance in ways that appear to be aggravating tensions in the region. I think the anxieties created by a prospective nuclear deal – and the adjustments in the region that it will necessitate – are contributing significantly to these tensions. The fact is that Israel and the GCC have benefited tremendously over the past 35 years by U.S. efforts to oppose and isolate Iran, and the nuclear deal signals a fundamental change in their position. Adjusting to it will prove very difficult and is likely to result in continuing, if not even more instability and conflict in the region, at least in the short term.

For original see: