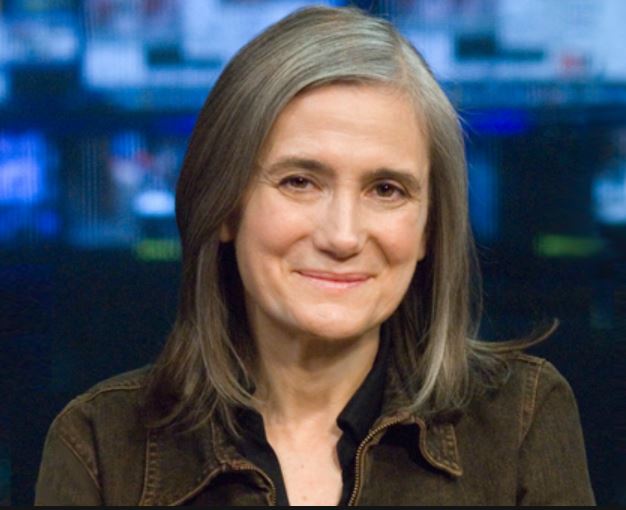

By Amy Goodman and Denis Moynihan

Tucked away on a side street in one of London’s toniest neighborhoods, just across the street from the sprawling department store Harrods, sits a brick, Victorian-era apartment building that houses the Ecuadorean Embassy. Julian Assange, the founder and editor of the whistle-blower website WikiLeaks, walked into this embassy on June 19, 2012, and hasn’t stepped foot outside since.

Ecuador granted him political asylum, but the United Kingdom refuses to grant him safe passage to leave the country. Instead, the U.K. wants to extradite him to Sweden to answer questions about allegations of sexual misconduct, although charges have never been filed. For close to three years, he has remained a prisoner in the embassy, denied even the hour of sunlight daily that most prisoners are guaranteed. For two years before that, he was either jailed or under strict house arrest in England, all without charge. When I went to London to interview him in the embassy this week, Assange asserted his belief that this pretrial phase is serving as both punishment and deterrent, and that Sweden is acting as a surrogate for the United States, which wants him jailed to stop the work of WikiLeaks.

Nevertheless, WikiLeaks continues, releasing groundbreaking information about potentially catastrophic conditions in Britain’s nuclear-weapons submarines, full chapters of the secret and intensely controversial Trans-Pacific Partnership trade treaty, and more. It was from within the embassy that Assange helped National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden escape Hong Kong after releasing millions of documents detailing U.S. government surveillance programs. En route to political asylum in Latin America, Snowden became stranded in the Moscow airport only after the United States canceled his passport. Russia then granted him temporary political asylum.

When the sexual-misconduct allegations surfaced in late 2010, Assange waited in Stockholm for the prosecutor to question him, then the charges were dropped. He had government permission to leave the country. It was only after he traveled to the United Kingdom that the charges were resuscitated by a second prosecutor. This second prosecutor, Marianne Ny, has had years to question Assange, either in person in London or via video link. Instead, she insisted that Assange be forcibly extradited, until a Swedish court ruled that she should interview him in London. She has now indicated that she will, but so far has not said when.

Assange, his lawyers and his supporters are concerned that, if he were extradited, Sweden would hand him over to the United States, where all signs point to a secret grand-jury investigation of him and WikiLeaks. “Julian would have gone to Sweden a long time ago had he gotten a guarantee from Sweden that they will not forward him to the United States for standing trial on the espionage charges,” said Assange attorney Michael Ratner, president emeritus of the Center for Constitutional Rights. Ratner explained: “Sweden has never been willing to give that guarantee. And Sweden has a very bad reputation of complying with U.S. demands, whether it was sending some people from Sweden to Egypt for torture or whether it’s guaranteeing people who are asylees in Sweden that they won’t be deported.”

Vice President Joe Biden called Assange a “high-tech terrorist,” and elected officials and pundits from both major parties have said publicly that he should be assassinated. Assange told me: “The U.S. case against WikiLeaks is widely believed to be the largest-ever investigation into a publisher. It is extraterritorial. It’s setting new precedents about the ability of the U.S. government to reach out to any media publisher in Europe or the rest of the world, and try and achieve a prosecution. They say the offenses are conspiracy, conspiracy to commit espionage, Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, computer hacking, conversion, stealing government documents.” The espionage charges, if they materialize, could come with the death penalty. Sweden, like most European nations, cannot extradite a person who might thereafter be put to death.

The statute of limitations will expire in August on all but one of the potential Swedish offenses for which Assange is wanted for questioning. The Swedish Supreme Court declined to quash the arrest warrant lodged against him in late 2010, in a 4-1 vote. Justice Svante Johansson, dissenting, wrote that Assange’s de facto detention was “in violation of the principle of proportionality.” Sitting across from me in the conference room of the small embassy that has for three years served as his home, his refuge and his jail, Assange told me, “We have no rights as a defendant because the formal trial hasn’t started yet. No charges, no trial, no ability to defend yourself … don’t even have the right to documents, because you’re not even a defendant.” His skin is pale from years without sunlight, matching his prematurely white hair. But his resolve is unbroken, and the leaks he originally sought to publish when he founded WikiLeaks almost 10 years ago are still reaching the light of day.