Interview with Arthur Conrad Kisitu

Arthur Kisitu is a Ugandan artist who decided to live for some time in a slum in Kampala, called Katanga – No Man’s Land. As a photographer he became involved in the lives of his neighbours and especially their children, documenting their stories.

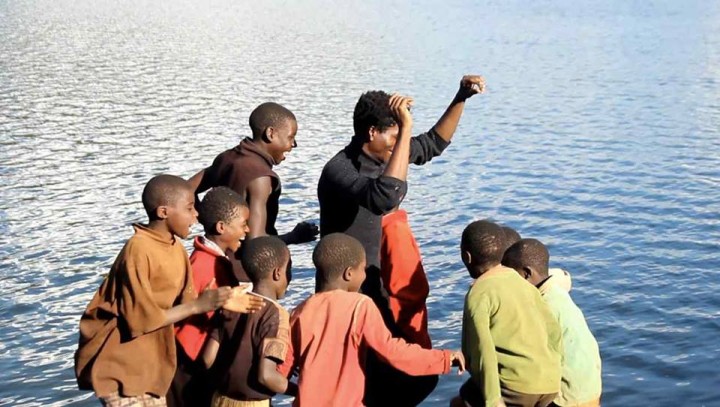

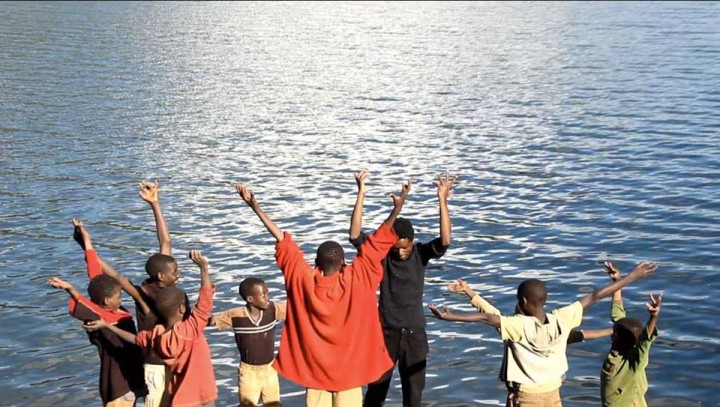

In 2013 he came to Berlin for an art exchange project between german and ugandan children, called Peace Matters. Returning to Uganda he continued working in Katanga but also involved children on the country side and of marginalized communities in his program. Now he developed with others a dance exchange program between children of the Katanga slum and children of the minority Batwa pygmy tribe who have been evicted from their homeland. Pressenza interviewed him on the situation of the children and the idea of the project.

Please tell us, what are the special difficulties that those children in Katanga and of the Batwa pygmy tribe face?

Batwa Pygmies are an Indigenous group of hunter-gatherer forest-dwelling people. Forced from their lands in the 1990’s, they now exist in settlement camps, and are denied access to their homeland by Authorities.

Their story is a sad one. They are indigenous to the Bakiga in Kabale. The community was forcefully evicted from Kisoro forests and Mount Mufumbira where they survived as hunter gatherers. It constitutes less than 1 % of Lake Bunyonyi’s population, where they have been resettled by the government.

The perception of them in servitude continues to dominate their lives. The births of Batwa are unrecorded and so with no legal status they have no rights to public amenities such as health services. For a long time the Batwa were not allowed to enter other people’s homes. They were seen to be backward, with no value. In their settlement camps, they have been reduced to a tourist attraction. Until recently there was no intermarriage with them. The Batwa who were once dependent on the now depleted forests as hunter gatherers are now mostly casual labourers.

They want their rights recognized and are demanding equal access to land, education and health services.

The 25,000 residents of Katanga Slum survive in extreme poverty. School rates are low, and there are few opportunities to escape the cycle of poverty.

Why dancing? People might think that there are more important things for the children, like going to school, getting health treatment and so on…

After residing in the slum for over 4 years, I set out on collecting thoughts from various inhabitants. Many times the inhabitants complained about the unfair representation of their story by the main stream media. Looking at these different points, I started photographing and interviewing the people.

I also learnt that human beings even in the most dire situation are not mere ‘’food machines” waiting for the next meal. True, one needs school, shelter, food to survive, later on to think but that does not make up for the emotional, mental and spiritual nourishment that makes a WHOLE being.

One of the aspects usually neglected when accessing people’s livelihood in poverty situations is LEISURE. In my country the children’s parks I knew as a child was given to commercial investors. Children being children tend to respond to this hunger for leisure in creative ways, sometimes better than the adults who tend to engage in more self destructive addictive leisure.

In their innocence children have a lot to teach us. Katanga was one of the first slums to loose the only children’s park that had been planned on this side of Kampala. Whereas most adults have taken on drinking sprees and abusive leisure lifestyles the children have adopted in a rather creative way to meet their need to play, dancing and recycling; their challenges notwithstanding.

What will happen when these two marginalized communities will meet?

In the course of documenting the Katanga story I sometimes follow children from the slum in Kampala, back to their villages when they go for Christmas or cultural festival reunions. In one of these instances I witnessed children fighting over which song to play and dance to. The ones from the city (slum) wanted to dance on pop urban music whereas the ones that were hosting them in the village preferred their traditional folk songs and dance.

My hope is that when the children meet we shall encourage them to teach each other the different way they dance. After learning each other’s dance, our team of professional choreographers will fuse the movements of the children into a harmonised dance routine that celebrates the diversity of culture; where traditional meets urban.

If time and resources allow we hope this routine will travel to other countries and continents in future as a testament that dance is a universal language that transcends barriers.

How did you start to get involved with the children’s situation in Katanga and the Batwa pygmy tribe?

Katanga, a former green belt, was one of few places that had been planned with a children’s park in the first plan of Kampala City. But when the current government came to power, the children’s land was given away as a gift to the veterans who fought the ‘liberation’ war.

With limited space to play, the children who make the majority of the slum population started improvising alternative spaces, and in their innocence dance became one of the games they play to pass time and have some leisure against all odds.

Against the backdrop of the initial Katanga-Berlin children’s art exchange that we realised in 2013, having learnt from its successes and the shortcomings I felt persuaded to believe that the cultural exchange dialogue that was experienced intercontinentally was also necessary for bridging the cultural generational gap that has been created by internal conflicts and forced migration between different local communities in Uganda.

In 2014, dance was included on our exchange program. I started a cultural exchange program between children in Katanga slum and their counterparts in Kabale, around Lake Bunyonyi. So far the emphasis has been on reaching the children in the Batwa community who are also

discriminated against by the other locals in Kabale.

Ekizino Dance is one of the few things that are shared by both the Bakiga (who make the majority Bunyonyi populace) and the minority Batwa. The only time the two communities seem to mix harmoniously is when they do the traditional dance together.

The distance between Kabale and Kampala (Katanga) is about 8 hours by bus. Then a two hour boat ride on lake Bunyonyi to reach the Batwa community that I am working with. Land rights disputes due to the resettlement continue to disrupt relations between the Batwa and surrounding community.

While these relations are just one aspect of the challenges that remain, we hope to use music and dance, for repairing relationships, promoting Batwa pride and involvement. I saw their shared passion for dance as an opportunity to bridge them! I believe that while dance is a reconnection to their history and traditions culturally, it can also prompt further collaboration locally, and globally.

If you want to know more about the project or support it, please contact Arthur Kisitu via email: theportraithome@gmail.com