Danny Katch measures the accomplishments and failures of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio against the expectations that his election would usher in real change.

THE CHICAGO mayoral election is getting national attention because incumbent Rahm Emanuel–a national political powerbroker endorsed by Barack Obama and super-rich to boot–has been forced into a runoff by Jesús “Chuy” García.

García is the opposite of Rahm in many ways: he’s a Mexican immigrant, a longtime Chicago resident and community leader–and not an arrogant, foul-mouthed, mean spirited, grudge-holding, banker asshole.

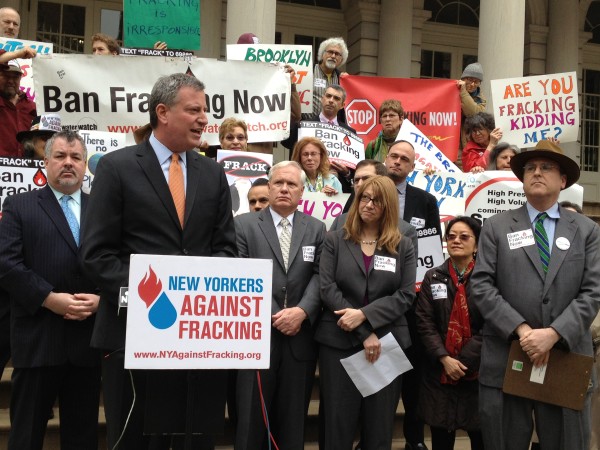

I understand the excitement that many people in Chicago feel about the possibility of defeating Rahm. In New York City, we had a similar moment in the fall of 2013 when Bill de Blasio won a landslide victory to become mayor, after a campaign in which he talked about how New York under billionaire Michael Bloomberg had become a “tale of two cities.” Bloomberg’s public image transformed within a matter of a few months from the wise rich guy who made the city a winner to the clueless rich guy who only cared about the city’s winners.

Once widely admired and feared, Bloomberg even became a bit of a punch line when he tried to challenge de Blasio’s claims about inequality, and instead came across like a doddering eccentric, complaining that poor people should be grateful for having air conditioning on the subways and urging “all the Russian billionaires to move here.” It was a good autumn in New York City, and I’m sure that springtime in Chicago would only be made lovelier by the sight of a defeated incumbent mayor sputtering in impotent Rahm-rage.

But there’s more to elections than wishing to see the miserable bums get thrown out. The experience of Bill de Blasio’s first year as mayor of New York City should make people on the left in Chicago think twice about supporting García’s campaign and voting for him. The problem isn’t that de Blasio has betrayed most of his campaign promises. It’s that for the most part, he’s tried to fulfill them–and in the process revealed how inadequate they were to addressing the inequality he said he would change.

There are many similarities between García’s campaign and de Blasio’s in 2013. Like de Blasio, who ran for office promising a moratorium on schools being closed and co-located with charters, García opposes many aspects of the corporate-backed “education reform” policies and calls for elected school boards.

Both candidates face a supposed budget crisis involving city unions–contracts left expired was the main issue in New York; what to do about underfunded pensions is the question in Chicago–that are the result of Emanuel and Bloomberg diverting revenues over the years into tax breaks and other corporate giveaways. Just as de Blasio did as a candidate, García is saying little about how he would deal with the money owed to city workers–in effect telling unions to trust him based on his past record of support of labor.

Another similarity between García and de Blasio is their approach to the issue of the police. García is calling for 1,000 more cops, but also repeats the classic sounds-nice-but-means-nothing line about more “community policing.” De Blasio campaigned against the NYPD’s “stop-and-frisk” racial profiling policy, but then chose as his new police chief Bill Bratton, architect of the Broken Windows policing strategy that led to stop-and-frisk in the first place.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

NOW THAT de Blasio has been in office for over a year, one word that’s often used to describe him is: nice. Definitely not a word that comes to mind about Bloomberg.

De Blasio seems to feel genuinely bad about the gaping inequality of a city that still belongs far more to Bloomberg and his Russian billionaires than to the majority of people who live in or close to poverty and can no longer afford rent anywhere less than an hour from midtown.

During his first year, de Blasio put real energy into passing laws meant to benefit that majority, from expanding the number of seats in pre-kindergarten classes to creating a municipal ID card for undocumented immigrants to guaranteeing sick days for all workers in the city.

These changes have been, well, nice. But unfortunately, for most New Yorkers, nice isn’t enough to pay the bills. There is no evidence that inequality–the chief theme of his election campaign–has been reduced during his time in office so far. In fact, 2014 saw a record number of children living in homeless shelters for at least one night–including a shockingly high one in every 17 Black children.

In order for de Blasio to reduce inequality and rewrite the tale of two cities in New York, he would need to do something to rich people that they might not consider very nice: Take some of their money and redistribute it to everyone else. But one year into office, de Blasio has shown that he’s better at empathizing with poverty than reducing it.

On the other hand, in an act of kindness to the city’s business owners, de Blasio has not fined a single one for violating his sick day law. Instead, his administration focused on mediation and spending $2 million on an outreach campaign about the new rules. As if a few hefty fines wouldn’t spread the word a lot quicker.

The appointment of Bratton as police chief another gesture of kindness to wealthy New Yorkers and tourists concerned that de Blasio’s liberal campaign rhetoric was a sign that the city might go back to the “bad old days” of graffiti and muggings spilling out beyond poor neighborhoods. By turning to Bratton, the new mayor sent a signal to the elites that the city would still be policed primarily for their benefit.

As a result of this policy of being nice to all sides, life under de Blasio is better for union leaders and community spokespeople–who receive far more access and kind words from City Hall than they did under Bloomberg. But it hasn’t changed nearly as much for the rank-and-file workers and residents that these officials represent.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

BECAUSE DE Blasio and García are unapologetically liberal, they are put forward as evidence–along with Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren on the national stage–of a new breed of progressives who are pushing the Democratic Party to the left after years of it being dominated by pro-business “moderates” like the Clintons.

But Chicagoans and everyone else should take note: If de Blasio is trying to challenge the conservative wing of his party–which in New York is embodied by Gov. Andrew Cuomo–he has a strange way of doing it.

Last year, Cuomo rejected de Blasio’s proposals to raise the city’s minimum wage to $13 an hour and to fund the expansion of pre-K with a tax on the rich. In response, de Blasio…not only endorsed Cuomo for re-election, but used his liberal credentials to help convince the Working Families Party to do so as well.

This was an awfully nice thing to do for Cuomo, but it hasn’t worked out so well for most other New Yorkers, who are now facing a Rahm Emanuel-style attack on public schools and teachers’ unions from their re-elected governor.

After 20 years of Republican mayors, even the minor reforms that de Blasio has managed to produce are probably considered enough by many progressives to validate their support for him. But we should also consider something that good businessmen like Bloomberg and Emanuel call “opportunity cost”–the potential benefits of staying outside of de Blasio’s campaign.

De Blasio’s successful campaign in 2013 reflected both the widespread sentiment against inequality popularized by the Occupy Wall Street movement and the successful efforts of unions and liberal organizations to steer that movement, or at least important parts of it, into the Democratic Party.

What if the unions that supported Occupy had followed its independent spirit and resisted settling for inadequate contracts that don’t even keep up with the cost of living, instead of being so eager to help their ally in City Hall get credit for “solving” the union crisis? Perhaps they would have taken to the streets to pressure de Blasio to find more money for over 300,000 city workers by taking the rich–which would just so happen to be a very direct way of addressing inequality.

What if the civil rights organizations that marched against stop-and-frisk during Bloomberg’s final years had joined radicals in the streets protesting de Blasio’s appointment of Bratton, instead of privately addressing their concerns in closed-door meetings with the mayor and police commissioner?

Those meetings don’t seem to have helped. Not only has the NYPD continued to patrol with violent vengeance–shown most notoriously in last summer’s murder of Eric Garner–but Bratton is now pushing his Broken Windows theory further into the dystopian realm of predictive policing. That’s a term you might not have heard of–but I bet you would have if more progressive organizations and civil liberties groups were protesting de Blasio the way they protested Bloomberg.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

“WHEN A kid gets to go to public school at [age] four instead of five, or a family gets affordable housing, or a parent gets a living wage and sick days, you’ve got a story to tell about how this approach to government made this city more equal and better…[even if] it turns out there is no movement in the Gini coefficient [which measures inequality].”

So said City Council member Brad Lander in an interview with Eric Alterman for his new book about de Blasio. It’s telling that Lander–a prominent Brooklyn liberal–is already lowering his expectations about reducing inequality to the intangible realm of anecdote and narrative after just one year of de Blasio being in office.

It’s not actually clear how many workers will get sick days if businesses aren’t punished financially for denying them. Nor is it clear that families will get affordable housing from de Blasio’s housing plan that depends on requiring private developers to include affordable units in new buildings.

As Sandy Boyer noted in a SocialistWorker.org article, “The problem with the policy of inclusionary zoning is that developers won’t build anything at all unless they’re guaranteed the spectacular profits that come with high rent and luxury apartments.” In other words, de Blasio’s plan for affordable housing rests on gentrifying more neighborhoods with unaffordable housing.

More generally, if the left abandons a vision for our cities that does involve drastic movement in the Gini coefficient, we’re doomed–which is something people on the left in Chicago need to consider in their upcoming mayoral runoff election.

SocialistWorker.org and its supporters did not endorse de Blasio in 2013–just as we never endorse candidates of the Democratic or Republican Parties–even as we cheered Bloomberg’s exit.

I imagine it will be harder for some to take that stand toward Chuy García this year in Chicago, because there’s a chance to defeat Rahm Emanuel, the bully who closed 50 schools to extract revenge after the Chicago Teachers Union fought off his onslaught with their 2012 strike. But casting a vote for a liberal Democrat–regardless of whether their opponent is a Republican reactionary or a pro-corporate member of their own party–gives up the political independence that any movement for social justice will need to win concessions from whoever is the victor.

The fight to take back cities like Chicago and New York City from the 1 Percent has to go further than replacing rich jerk mayors with nicer ones. It requires building political alliances and social movements dedicated to much more fundamental and lasting change.