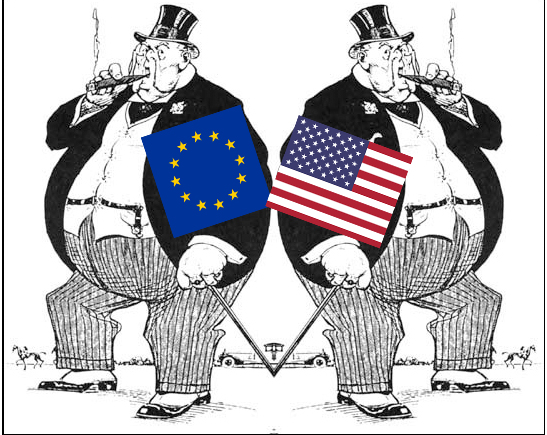

This bill of corporate rights threatens to blow the sovereignty of parliament unless it can be stopped

By George Monbiot for The Guardian

On this day a year ago, I was in despair. A dark cloud was rising over the Atlantic, threatening to blot out some of the freedoms our ancestors lost their lives to secure. The ability of parliaments on both sides of the ocean to legislate on behalf of their people was at risk from an astonishing treaty that would grant corporations special powers to sue governments. I could not see a way of stopping it.

Almost no one had heard of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the US, except those who were quietly negotiating it. And I suspected that almost no one ever would. Even the name seemed perfectly designed to repel public interest. I wrote about it for one reason: to be able to tell my children that I had not done nothing.

To my amazement, the article went viral. As a result of the public reaction and the involvement of remarkable campaigners, the European commission and the British government responded. The Stop TTIP petition now carries more than 750,000 signatures; the 38 Degrees petition has 910,000. Last month there were 450 protest actions across 24 member states. The commission was forced to hold a public consultation about the most controversial aspect, and 150,000 people responded. Never let it be said that people cannot engage with complex issues.

Nothing has yet been won. Corporations and governments – led by the UK – are mobilising to thwart this uprising. But their position slips a little every month. When the British minister responsible at the time, Ken Clarke, responded to my first articles, he insisted that “nothing could be more foolish” than making the European negotiating position public, as I’d proposed. But last month the commission was obliged to do just this. It’s beginning to look as if the fight against TTIP could become a historic victory for people against corporate power.

The central problem is what the negotiators call investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). The treaty would allow corporations to sue governments before an arbitration panel composed of corporate lawyers, at which other people have no representation, and which is not subject to judicial review.

Already, thanks to the insertion of ISDS into much smaller trade treaties, big business is engaged in an orgy of litigation, whose purpose is to strike down any law that might impinge on its anticipated future profits. The tobacco firm Philip Morris is suing governments in Uruguay and Australia for trying to discourage people from smoking. The oil firm Occidental was awarded $2.3bn in compensation from Ecuador, which terminated the company’s drilling concession in the Amazon after finding that Occidental had broken Ecuadorean law. The Swedish company Vattenfall is suing the German government for shutting down nuclear power. An Australian firm is suing El Salvador’s government for $300m for refusing permission for a goldmine over concerns it would poison the drinking water.

The same mechanism, under TTIP, could be used to prevent UK governments from reversing the privatisation of the railways and the NHS, or from defending public health and the natural world against corporate greed. The corporate lawyers who sit on these panels are beholden only to the companies whose cases they adjudicate, who at other times are their employers.

As one of these people commented: “When I wake up at night and think about arbitration, it never ceases to amaze me that sovereign states have agreed to investment arbitration at all … Three private individuals are entrusted with the power to review, without any restriction or appeal procedure, all actions of the government, all decisions of the courts, and all laws and regulations emanating from parliament.”

So outrageous is this arrangement that even the Economist, usually the champion of corporate power and trade treaties, has now come out against it. It calls investor-state dispute settlement “a way to let multinational companies get rich at the expense of ordinary people”.

When David Cameron and the corporate press launched their campaign against the candidacy of Jean-Claude Juncker for president of the European commission, they claimed that he threatened British sovereignty. It was a perfect inversion of reality. Juncker, seeing the way the public debate was going, promised in his manifesto that “I will not sacrifice Europe’s safety, health, social and data protection standards … on the altar of free trade … Nor will I accept that the jurisdiction of courts in the EU member states is limited by special regimes for investor disputes.” Juncker’s crime was that he had pledged not to give away as much of our sovereignty to corporate lawyers as Cameron and the media barons demanded.

Juncker is now coming under extreme pressure. Last month 14 states wrote to him, privately and without consulting their parliaments, demanding the inclusion of ISDS (the letter was leaked a few days ago). And who is leading this campaign? The British government. It’s hard to get your head around the duplicity involved. While claiming to be so exercised about our sovereignty that it is prepared to leave the EU, our government is secretly insisting that the European commission slaughter our sovereignty on behalf of corporate profits. Cameron is leading a gunpowder plot against democracy.

He and his ministers have failed to answer the howlingly obvious question: what’s wrong with the courts? If corporations want to sue governments, they already have a right to do so, through the courts, like anyone else. It’s not as if, with their vast budgets, they are disadvantaged in this arena. Why should they be allowed to use a separate legal system, to which the rest of us have no access? What happened to the principle of equality before the law?

If our courts are fit to deprive citizens of their liberty, why are they unfit to deprive corporations of anticipated future profits? Let’s not hear another word from the defenders of TTIP until they have answered this question.

It cannot be ducked for much longer. Unlike previous treaties, this one is being dragged by campaigners into the open, where its justifications shrivel on exposure to the light. There’s a tough struggle to come, and the outcome is by no means certain, but my sense is that we will win.