By Joel Jaeger

UNITED NATIONS, Aug 18 2014 (IPS) – The Arms Trade Treaty is about to provide the biggest shake-up to conventional arms trade transparency since the end of the Cold War.

U.N. officials and civil society experts expect the quality and quantity of reports on the international arms trade to increase as the current platform, the U.N. Register of Conventional Arms, is augmented by the forthcoming Arms Trade Treaty.

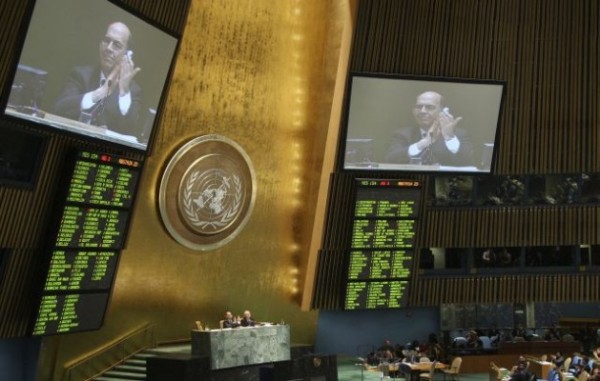

Established by the U.N. General Assembly in 1991, the U.N. Register requests that countries produce official reports of their arms imports and exports each year. The information is then published for all to see on a U.N. website.

However, reporting to the U.N. Register is purely voluntary.

Daniël Prins, chief of the Conventional Arms Branch at the U.N. Office for Disarmament Affairs, told IPS that “most countries in the world have at one time or another reported to the U.N. Register, but on a year on year basis we don’t receive the complete picture.”

Glancing through the U.N. Register’s yearly summaries, it is easy to see that something is missing. According to the data in the Register, 760 battle tanks were exported in 2012, but only 446 were imported.

Exporters of weapons are generally more willing to provide information than importers, according to Paul Holtom, deputy director of the Centre for Peace and Reconciliation Studies at Coventry University.

“There is a culture of secrecy in a number of states,” Holtom told IPS, specifically mentioning arms importers in the Middle East and Africa. “In general, they don’t want to produce any information for the public domain.”

Countries have also blamed their incomplete reports on unavailability of information, lack of resources, poor inter-agency cooperation, and lack of time.

Participation in the U.N. Register peaked in 2001, when 126 countries submitted national reports. By 2012 it had dropped to 72 countries.

Enter the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), which was approved by the U.N. General Assembly on Apr. 2, 2013 and is expected to enter into force in late 2014 or early 2015. The ATT is much more than just a transparency convention, since it regulates arms transfers at a broader level, but it does specifically address reporting.

Unlike the voluntary U.N. Register, the ATT’s reporting requirements are legally mandated.

Countries that ratify the ATT “have an obligation as a state party to produce an annual report on imports and exports,” Holtom said.

The ATT’s reporting requirements include all seven categories of weapons from the U.N. Register: battle tanks, combat vehicles, large calibre-artillery systems, combat aircraft, attack helicopters, warships, and missiles and missile launchers.

But the ATT goes one step further by requiring reports on small arms and light weapons as well. With the U.N. Register, small arms were only a secondary consideration.

Civil society members see the inclusion of small arms in the ATT as a much-needed development, since the majority of conflict deaths are caused by small arms.

“The Arms Trade Treaty has the potential to increase the level of reporting on small arms and light weapons, and to improve comprehensiveness and level of detail,” Sarah Parker, a senior researcher at the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey, told IPS.

However, Parker also cautioned that the scope of the ATT’s categories will need to expand to accommodate new weapons and technologies.

Daniël Prins says the ATT has the capacity to keep up with the times.

“Of course it doesn’t include every item that militaries use – trucks for instance – but all major weapons systems are covered,” he said.

“The treaty has provisions for changing it, for adaption, at least six years after entry into force. Of course, you need a willingness of its members to go there, but it’s perfectly possible to keep the treaty’s scope up to date with technology.”

The U.N. Register and the ATT’s reporting instruments will run in parallel.

According to Holtom, who served as the consultant for a 2013 group of governmental experts on the U.N. Register, getting rid of the Register would mean losing valuable information from countries that are not ready to start reporting for the ATT.

“Russia and China… report regularly to the U.N. Register,” he told IPS, but “they’ve made no signal of having any intention in the near future to sign the ATT, let alone ratify.”

One hundred and eighteen countries have signed the ATT, and 43 states have ratified. The treaty officially enters into force three months after the fiftieth ratification.

“I’m surprised that it’s actually been so quick,” Holtom said.

A 2015 entry into force was originally seen as a best case scenario, but it is soon likely to become a reality.

Prins expressed the expectation that the number of ratifications will grow well over the minimum of 50. The immediate goal should be to have more than half of the U.N.’s members be a State Party — a fuller embrace of the treaty will take years of concerted action, but is very much possible, he said.

Of course, the ATT will have less of an impact if the leading importers and exporters are not on board. The European Union is committed to the treaty, but the United States and Russia seem disinclined to join.

President Obama signed the treaty last year, but a bipartisan majority of Congress has come out in opposition to ratification. Still, even outside the ATT, the U.S. does not have total freedom to export arms as it chooses.

“The U.S. argues that it already has one of the most rigorous export control systems in the world,” Parker told IPS. “I think this is legitimate, frankly.”

India and China, the two largest importers of conventional arms, both abstained from the General Assembly’s vote on the ATT in 2013. India pledged to assess the treaty’s impact on its defence, security, and foreign policy interests. China’s abstention was procedural, as it did not object to any specifics of the treaty.

Preparation for the ATT’s entry into force has already begun.

The U.N. Office for Disarmament Affairs has established a trust fund to assist countries with implementation of the treaty, Prins told IPS.

States parties will establish specific procedures for reporting as the ATT system develops over the years.

“Mexico has offered to host the first conference of states parties, which will likely take place next year, sometime between April and September,” Parker said.

Stepping back from the technical details, on the broader scale, does arms trade transparency actually deter war?

According to Paul Holtom, “transparency on its own is insufficient for addressing conflict. What you really want to have is transparency connected with responsibility and accountability.”

The public dissemination of export and import numbers should spur active national debates on the merits of particular weapons transfers, Holtom believes.

Public debates could be also be initiated by an independent observer body.

“There are plans for something called an ATT monitor,” Parker told IPS.

NGOs, civil society and academic institutions in the ATT monitor would scrutinise where states were transferring weapons and evaluate the advisability of the export based on the circumstances of the importing country, she said.

Whatever happens, it is clear that the ATT will be an improvement over the U.N. Register.

Take the recent decisions by the United States and France to arm the Kurdish militia in Iraq, for example. Neither country has indicated the number of weapons being transferred.

Because the Kurds are a sub-national group, these transfers do not fall under the scope of the U.N. Register, which only applies to state-to-state exchanges. However, according to Holtom, the ATT requires transparency on transfers to non-state actors as well. Under the ATT, the United States and France would need to report those transfers.

The U.N. Register was developed in the context of the immediate post-Cold War. As the nature of warfare shifts from international disputes to conflicts involving sub-state armed groups, the ATT will bring arms trade transparency into the present.

Edited by: Kitty Stapp