They know their lives are at risk, yet each year thousands of people from Africa, the Middle East and beyond — war refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants — leave their homes and try to reach the promised land of Europe. On the third of October 2013, more than 360 would-be emigrants drowned off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa. A catastrophe of this dimension grabbed the media’s attention for a while and won the sympathy of the general public.

In response, later that month, the European Council decided to implement measures aimed at preventing a repeat of such a tragedy at the European Union’s borders .The Council called for strengthening the EU’s border security co-ordination system, Frontex, more formally known as the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union. And the Europe-wide surveillance system Eurosur began operations on December 2, 2013. Thus, once again, a large tragedy spurred real, if belated, action.

Well-intended though they doubtless were, these measures only address the tip of the migration iceberg. Little is known about how many men, women and children actually have lost their lives on their journey to Europe. Believing that policy unsupported by facts cannot be optimal, a consortium of European journalists committed themselves to systematically assembling and analyzing the data on the deaths of Europe’s would-be migrants. The Migrants’ Files project is partially funded by the European non-profit organization Journalismfund.eu.

Data sources

By compiling rigorous datasets from various sources, The Migrants’ Files team aims at creating a comprehensive and reliable database on migrants’ deaths. Principal data sources for this effort include United for Intercultural Action, a non-profit whose network comprises over 550 organizations across Europe, and Fortress Europe, founded by the journalist and author Gabriele Del Grande, which also monitors the deaths and disappearances of migrants to Europe. The Migrants’ Files’ database also uses data from Puls, a project run by the University of Helsinki, Finland and commissioned by the Joint Research Center of the European Commission.

A consistent methodology is applied to all data, starting with so-called “open-source intelligence” (OSINT). Originated by the intelligence services, this approach collects data from publicly available sources such as media reports, government publications and grey literature. In the case of The Migrants’ Files, the number migrants who die while seeking refuge in Europe is obtained by monitoring real-time global news on asylum seekers, migration and human trafficking activities in and around Europe.

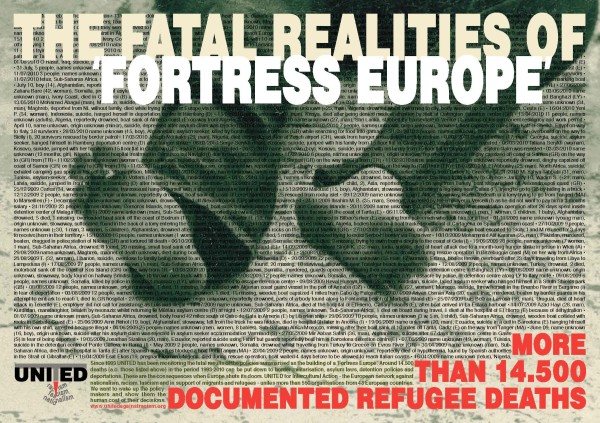

United for Intercultural Action monitored emigrant fatalities from 1993 until 2012, documenting about 17,000 deaths. Gabriele Del Grande reports more than 19,000 deaths since 1988. The database of The Migrants’ Files covers the period from January 1, 2000, until today.

The journalists of The Migrants’ Files noted that the various data sources often lacked compatibility since each organization structures its intelligence differently. This required extensive data cleaning and fact-checking, using OpenRefine, an open source analysis tool. In a second stage, The Migrants’ Files journalists established a database on Detective.io, a web-based tool specifically designed to support information gathering efforts for large-scale investigative reporting projects.

Early in the process of establishing The Migrants’ Files’ data methodology, sixteen students from the Laboratory of Data Journalism at the University of Bologna, Italy, contributed valuable fact-checking of more than 250 incidents, supervised by Prof. Carlo Gubitosa.

The Migrants’ Files database of emigrant deaths now structures the data according to name, age, gender and nationality. Every fatal incident is recorded with its date, latitude, longitude, number of dead and/or missing as well as the cause.

Margins for error

Overcoming the issue of data compatibility, The Migrants’ Files journalists have managed to create the most comprehensive survey of European migration fatalities available today. That said, the project team is aware that biases inherent in every dataset cannot be fully eliminated.

What’s more, aggregating several sources of data can easily produce duplicates. When duplicates are detected are manually removed, one at a time. Accuracy is laborious.

Beyond duplicates, some individuals had been registered as missing, say, identified by survivors of a shipwreck. If a body washes ashore in another location days or weeks later, it is virtually impossible to assign it to an earlier incident. And some fatal incidents have not been reported in any form. Hence, other sources of intelligence, such as testimonies, are carefully reviewed and double-checked before registering an incident in the database. Nonetheless, there is no getting around the fact that some individuals and events cannot be documented since no evidence offers confirmation. This sad reality cannot be redressed, rendering all fatality estimates conservative. The true numbers of dead are doubtless higher than recorded.

Moreover, assessing the geolocation and mapping the registered incidents imposes other kinds of difficulties. The map of The Migrants’ Files also presents incidents far from European borders due to the methodology used. For example, a boat capsized on its route from Algeria to Spain can be geolocated in Algeria and at the country’s center.

The Migrants’ Files is ongoing. The team continues to collect intelligence on the deaths of Europe’s would-be emigrants. The project aims to further improve the quality of its data, to shed more light on the situation of emigrants seeking refuge in Europe and to consistently track European asylum and migration policy, particularly because the broader media often ignores the issue until another large-scale emigrant tragedy thrusts it back to the top of the news cycle.