CARACAS, Apr 12 2014 (IPS) – Government and opposition leaders in Venezuela held a nationally televised debate as a first step to working towards solutions for the economic, social and political crisis marked by over two months of protests.

The demonstrations and the crackdown have cost 41 lives, including those of seven police officers, and left 600 injured and 2,300 arrested – with 100 still behind bars – and 70 reports of torture.

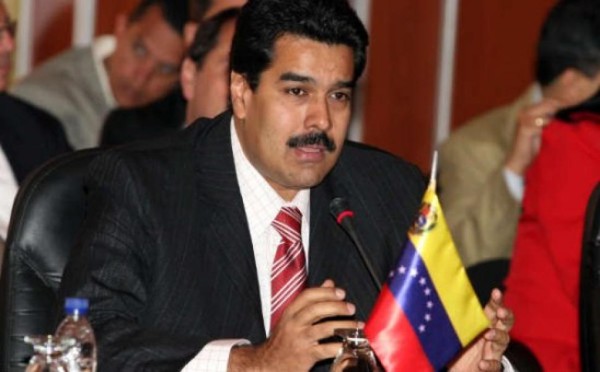

Foreign ministers Luiz Figueiredo of Brazil, María Ángela Holguín of Colombia, and Ricardo Patiño of Ecuador, and the Vatican apostolic nuncio to Venezuela Aldo Giordano, brokered the six-hour talks hosted by President Nicolás Maduro Thursday night.

The president issued a call “to acknowledge each other and reject the pressure from those who want to impose extreme ways, of violence.” He also called on his adversaries “not for a pact or negotiations, but for a willingness for peace. We want a model of coexistence, of tolerance.”

The leaders of the Mesa de Unidad Democrática (MUD – Roundtable of Democratic Unity), a multicolour coalition of opposition parties ranking from the right wing to former leftist guerrillas, met with Maduro and his closest associates in the Miraflores presidential palace.

The main political instigators of the protests, including the jailed Leopoldo López, boycotted the talks.

The university students who started the protests in the capital and dozens of cities around the country did not take part in the meeting. Their main leader, Juan Requesens of the Central University in Caracas, warned that “we will continue our peaceful protests, because there are many reasons to protest.”

“The uncertainty and scepticism surrounding this first meeting will continue while people wait for the government, above all, to send out concrete signals of change in its measures and policies,” Carlos Romero, a graduate studies professor of political science, told IPS.

The protests broke out on Feb. 4 in the southwest city of San Cristóbal and spread to Caracas on Feb. 12, driven by university students who complained about crime on their campus.

The demonstrations grew as the hardline opposition began to demand an end to Maduro’s government, and marches and roadblocks often turned into violent clashes with the military and police and government supporters.

The protests, in which mainly middle-class demonstrators are backing the students, are happening against a backdrop of economic difficulties such as a nearly 60 percent annual inflation rate, scarcity of some food and other basic items, and long, exhausting queues of people waiting to buy products sold under a rationing system.

The high crime rates – more than 24,000 homicides were committed in 2013 – and the poor functioning of services like electricity, water and public hospitals, especially outside of Caracas, are also fuelling the protests.

On Thursday Apr. 10, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) said in a preliminary report that Venezuela has the second-highest murder rate in the world, with 53.7 homicides per 100,000 population.

Maduro, the governing United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) and leaders of the armed forces say they managed to block a plan backed by Washington to subvert the constitutional order and overthrow the government, with the help of the protests.

The president won the Apr. 14, 2013 elections after Hugo Chávez, who governed the country since 1999, died of cancer on Mar. 5.

Like a snowball effect, the initial reasons for the protests gave way to others, such as the demand that the deaths of people killed – mainly shot – at the roadblocks be investigated, that those responsible for human rights violations be held to account, and that the detainees be released.

The people still in jail include López and two opposition mayors, from San Cristóbal and from a city in the central state of Carabobo, who the Supreme Court removed from office in what was described by some as a summary trial. They were sentenced to a year in prison for ignoring orders to remove the roadblocks set up by protesters in their municipalities.

The release and restitution of the mayors was another demand set forth by the opposition in the meeting that ended in the early hours of Friday morning.

The opposition is also demanding that armed irregular civilian groups de disarmed.

In the talks, the government and MUD leaders outlined their conflicting visions of the country, the economy and democracy, with each side sounding a litany of complaints about the conduct of the other over the past 15 years.

“The prospects for reaching an agreement on the underlying questions are still remote, because of the conflicting visions, at the end of a first meeting which seemed more like group therapy than a dialogue or negotiations,” political science professor José Vicente Carrasquero commented to IPS.

The foreign minister of Ecuador, Patiño, said that “despite the difficulties, the meeting was positive; a catharsis was necessary; they needed to meet face to face.”

MUD coordinator Ramón Aveledo, a Christian Democratic politician, proposed dates for further talks, starting with a meeting between the government and the students.

MUD called again for respect for the 1999 constitution, the separation of powers, measures against crime, and an amnesty law.

The opposition’s proposed amnesty would involve the release of those in prison for the current protests and others serving lengthy terms for involvement in the violent demonstrations that led to a short-lived coup that toppled Chávez for 48 hours. Thursday was the 12th anniversary of the coup.

Maduro designated a government commission to evaluate the issues and the next meetings. One of the members, Foreign Minister Elías Jaua, said “the president has the mandate of the people and can’t just do what MUD wants.”

The governor of the state of Miranda, Henrique Capriles, the leader of the moderate opposition who was Maduro’s rival in last year’s elections, also took part in the debate. “Things have to change, or this will burst,” he said at the end of his address in the meeting.