Op-ed published on 11 September on Bío Bío Nacional’s website

Forty years after the Chilean military coup of 11 September 1973, Latin America’s conscience is still haunted by memories of the dust clouds from the attack on La Moneda, the presidential palace. Salvador Allende’s death and the rubble left by the bombardment endure as symbols of democracies crushed by the claws of Operation Condor, just as certain open wounds still endure. In the absence of justice, the time has come for repentance, albeit belatedly. But not, with few exceptions, in the ranks of the media.

The Brazilian media giant Globo took the plunge on 31 August by publicly acknowledging in its daily newspaper that its support for President João Goulart’s removal in a military coup on 31 March 1964 was a “mistake.” “It was the Cold War and we thought we were saving democracy,” the newspaper said. But Argentina’s Clarín and Chile’s El Mercurio have yet to offer a mea culpa, although they also backed their countries’ armed forces when they seized power by force. The golden rule for them is business as usual, it seems.

Globo’s act of contrition has not diminished its share of the Brazilian market. In Chile, El Mercurio and the Copesa media group continue to be the sole beneficiaries of the government’s support for the media, worth 5 million dollars a year. And Clarín continues to dominate Argentina’s airwaves, refusing to surrender any of its frequencies as required by the new Broadcasting Services Law – also known as the SCA or Media Law – whose full application is still on hold pending a supreme court decision.

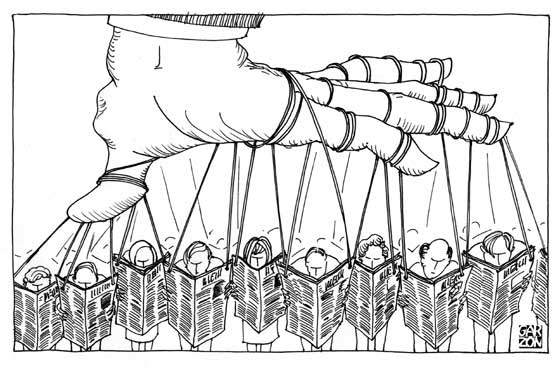

The media regulation introduced by the various currents of the South American left in the 2000s (in Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador and Uruguay) is understandable in the light of the heritage of the Operation Condor years. Censorship and terror have ended but it cannot be said that media pluralism prevails, not real pluralism. The concentration of media ownership that was consolidated under the dictatorships has continued unchallenged since the return to democracy.

This was one of the issues raised by the Chilean students who took to the streets in large numbers in 2011, and by the many participants in last June’s “Brazilian Spring” protests. And sometimes history pauses in its advance, as it did in Venezuela in 2002, Honduras in 2009 and Paraguay in 2012, when leading privately-owned media were accomplices to coups or coup attempts that should have been a thing of the past.

The promotion of new media legislation has logically often met with opposition from the affected media. It is true that some governments have encouraged polarization that has hindered public debate. It is also true that some legislation, as in Ecuador, has tended to impose undesirable controls on the media and media content, as well as a fairer distribution of broadcast frequencies.

But a redefinition of broadcasting, one that takes account of the region’s burgeoning alternative media and community radio stations, is badly needed. With the backing of the UN and OAS special rapporteurs, Argentina and Uruguay are dismantling the old, obsolete regulatory systems that were a hangover from the dictatorships. But the old status quo still prevails in Brazil and Chile.

It is an irony of history that the supporters of Pinochet’s coup who wanted to “avoid another Cuba” must now acknowledge the truth of a comment by a Chilean journalist who spent many years in exile: “Chile is just like Cuba, no opposition newspapers are to be seen on the newsstands.” So, for goodness’ sake, dear media shareholders, do not invoke “media freedom” in defence of your dividends.

Christophe Deloire, Reporters Without Borders secretary-general

Benoît Hervieu, Reporters Without Borders Americas Desk