By Marta Molina April 29, 2013

To commit an act of civil disobedience requires one to let go of their fear, understand their enemy and their enemy’s power. It must be rooted in good strategy and be supported by an organized group. But most importantly, the action must help to build alternatives to the power structures it confronts.

This type of action is exactly what 38-year-old Enric Durán, a Catalán from a town near Barcelona, accomplished when he expropriated 500,000 euro — more than $650,000 USD— from Spanish banks to protest the perversion of the banking culture. He gave this money to various social movements that are building alternatives to capitalism, including the Catalán Integral Cooperatives, a group that is calling for a radical societal transformation called the Integral Revolution. He also financed the publication Crisis, in which he revealed his act of banking disobedience on September 17, 2008.

“It represents a new type of civil disobedience, reflective of the times we are living in,” he wrote in Crisis. “When finances and speculation dominates our society, what better way to [fight back than] by stealing from those who steal and redistributing the money among the groups that denounce the situation and work to build alternatives?”

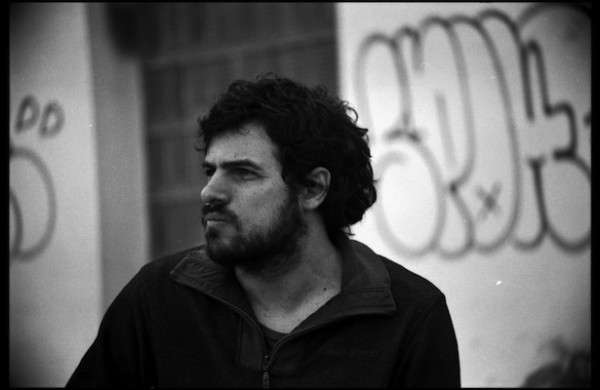

Durán’s action continued this year, when he disobeyed the judicial system and went into hiding, prompting the Spanish police to issue a warrant for his arrest in late March. Recently, Waging Nonviolence was able to speak with the ensconced Durán online through Skype for more than an hour. He explained his act of disobedience and the ways that alternatives are building momentum in Spain, other parts of Europe and across the world.

The act

In 2006, before Spain’s economy began to collapse, Durán had already begun building a strategy to condemn the banks. He wanted to expose the financial industry’s system of lending money that it didn’t have and its system of converting imaginary money into consumer debt. He applied for credit from all of the banks that he could. He constructed stories about his solvency, saying that he had stable work, consistent cash flow, and that he had no other large debts. In total, Durán received 68 loans from 39 banks totaling 492,000 euros.

Then came Durán’s act of resistance.

“I just stopped paying all of the debts,” he explained. “I took the money out of my accounts, and I made public what I had done in September of 2008. During that whole process I was investing that money in projects that work to create alternatives to capitalism, culminating with the publication of Crisis and a second newspaper, We Can Live Without Capitalism!”

The mainstream media dubbed him the “Robin Hood of the banks,” but his inspiration really came from other anarchists and members of revolutionary social movements. One is Basque anarchist Lucio Urtubia, who used traveler’s checks to orchestrate a multimillion dollar fraud against Citibank in the 1970s. Urtubia’s action caused Citibank’s stocks to plummet, while he — like Durán — used the money to finance a host of revolutionary and anarchist organizations. Unlike Urtubia, Durán made his action public precisely to defend the legitimacy of what he did to society. The Zapatista movement was another inspiration for Durán. In an interview, he called it one of the few movements that has truly practiced autonomy and “not accepting power, and not trying to justify something before those from above.”

The right to rebel

Durán draws on a human-rights framework, as well as the host of international proclamations enshrining these rights, to explain his direct actions. In December of 2011, he wrote a letter calling for mass civil disobedience through financial insubordination. “Human rights are the bare minimums,” he wrote. “They cannot be negotiated, and if they are not met, they can only be defended with one other right, and that’s the right to rebellion.”

He elaborated on his right to rebellion during an interview. “When the government does not act in the interest of the people, and it benefits only a small minority, the people’s greatest right is to disobey and rebel against that injustice,” he said. “Given that this has been happening for many years — but especially in recent years — in terms of benefits going to those in power, to the banks, and hurting the majority of the population, we believed this was the right time to recall our right to disobey.”

This rebellion, he explained, is not simply about disobeying a law in order to improve it. Rather, he said, “we don’t recognize [this law] as our own, so in our shift towards another society, we won’t be a part of the system they try to impose on us, and we disobey it.”

For Durán, this refusal extended beyond the banking sector’s concept of debt. Earlier this year, he also refused to recognize the validity of the Spanish judicial system’s case against him. He submitted 23 testimonies justifying the “state of necessity,” a legal clause that absolves one from punishment if the law was broken for a greater good. Then he went into hiding.

“Right now I have to be hidden, not out of fear but because of strategy,” he said, explaining that he was more useful to the movement if he is in hiding than if he is in a jail cell.

His disappearance inspired a campaign aimed at investigating and developing strategies to create alternatives to the current judicial system. Supported by the Cooperative for Social Self-Financing Networks and the Integral Catalán Cooperative, which Durán helped finance, more than one hundred people raised money and became involved in this campaign. On April 1, as Europeans watched Cyprus and the E.U. attempt to seize portions of Cyproits’ bank accounts, the group also began encouraging Spaniards to cancel their accounts, investment funds and pensions, to sell their stocks and to move their money to cooperatively run banks.

Even though he is in hiding, Durán speaks to reporters in part because he believes that power is accustomed to — and indeed, thrives on — people’s self-censorship.

“But when we act with strength and courage, power sometimes doesn’t know how to respond,” he said. “It takes a step backwards, because it recognizes the illegitimacy in attacking our well-being. That’s why it is so key that we affirm ourselves and what we want, even in the face of risks.”

The original article can be found on the Waging Nonviolence website, here.