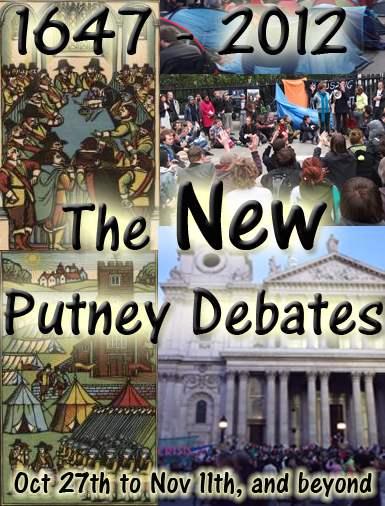

- Changing times, same needs: The Putney Debates and London Occupy Assemblies

- In 1647 England witnessed a remarkable moment, a revolutionary moment in which people demanded universal human rights, the Army attemped to become democratic electing its officers and a spiritual challenge to established power combined with demands for access to land for ordinary people. We reproduce here the background for The New Putney Debates which will look at what has been achieved, what has not, and what can be done to rekindle the spirit of this most interesting historical moment.

Unfinished business of England’s October revolution

In the early days of October some 365 years ago, the Levellers movement began drafting two documents that would become the political high points of the English Revolution which had developed out of the civil war between King Charles I and Parliament.

The Case of the Armie Truly Stated was published on October 15, 1647 and by the end of the month, the Levellers had also produced An Agreement of the People for a firm and present peace upon grounds of common right.

Astonishingly, for the times, the New Model Army led by Oliver Cromwell had yielded to pressure to allow for a Council of the Army to meet. It was made up of officers and rank-and-file soldiers, whose representatives were thenceforth known as Agitators.

With the army camped at Putney and Charles I held prisoner, the civil war seemed over. What the two documents set out was a constitutional settlement that had no place for monarchy or the House of Lords. Moreover, they emphasised that power should lie with the people and that the vote be given to all “free men”, with parliaments elected every two years.

These earth-shaking documents came before the Council of the Army at stormy debates held at a church in Putney that lasted from October 28 until November 9. The Case of the Armie Truly Stated declared:

Whereas all power is originally and essentially in the whole body of the people of this nation, and whereas their free choice or consent by their representers is the only original or foundation of all just government, and the reason and end of the choice of all just governors whatsoever is their apprehension of safety and good by them, that it be insisted upon positively, that the supreme power of the people’s representers, or Commons assembled in Parliament, be forthwith clearly declared.The Agreement stated:

That the power of this, and all future Representatives of this Nation, is inferior only to theirs who choose them, and doth extend, without the consent or concurrence of any other person or persons, to the enacting, altering, and repealing of laws, to the erecting and abolishing of offices and courts, to the appointing, removing, and calling to account magistrates and officers of all degrees, to the making war and peace, to the treating with foreign States, and, generally, to whatsoever is not expressly or impliedly reserved by the represented to themselves.

What the Levellers put on the table were questions that still resonate today about the relationship between rulers and ruled, between property and politics, the independence of the legal system and the nature of power and the state.

It was Cromwell’s son-in-law Henry Ireton whose response at Putney summed up the bourgeois nature of the revolution that brought an abrupt end to absolute monarchy and created the social conditions for the subsequent emergence of capitalism.

Ireton said the vote was rightly restricted to those who have “a permanent fixed interest in this kingdom”, namely “the persons in whom all land lies, and those in corporations in whom all trading lies”. He added that “liberty cannot be provided for in a general sense if property be preserved.” Sounds very much like the corporatocracy that rules Britain today!

Although representation through the vote was eventually conceded (but not completely until 1929), the sovereign power of the people mooted by the Levellers (and the proto-communist Diggers) remains as out of reach as ever.

The English Revolution of the 1640s erupted because the relationship between the state and the people had broken down in an irretrievable way. You could argue that the existing relationships between the capitalist state and the people is equally fractured. The state rules for and on behalf of corporations and banks and against the people.

Occupy London working groups are holding a series of events as the New Putney Debates this month and next, and on November 17 an Assembly will be held in London to work on a new Agreement of the People. Both events provide opportunities to complete the unfinished business of England’s October Revolution.

Paul Feldman